Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

FASD / FAS/E is not about having a different looking face – which disappears with age, making diagnosis as an adolescent or adult very difficult, or about being somewhat shorter than normal. It is about having deceptively significant brain damage, even in the absence of mental handicap, with enormous implications for function in all adult domains. Its impact on the ability to parent cannot be overstated.

People with FASD have many neurobehavioural problems which inter-relate to produce profound problems with accurately processing information and relating to the world around them. Those with the greatest impact on adult functioning are as follow:

Problems with cause and effect relationships and impulse control

Cause and effect can best be defined as prediction. It is somewhat like having your own crystal ball through which one can accurately foresee the future – both in terms of immediate mid-term, and long-term events. Without the neurological ability to do this, events remain disconnected from one another, and the affected person has great difficulty learning from experience or grasping consequences. They are often unable to understand that their behaviour has an effect on another person and will be bewildered by, or even hostile to our reaction to what they have or have not done. They are frequently described as having no conscience or showing no remorse – which is really a reflection of the problem, and not the problem itself.

Cause and effect is also intimately connected to the ability to control impulses. For people with normal cause and effect reasoning and impulse control, the two are seen as a three-part intermingled thought process: action, reflection, consequence, or impulse, reflection, action/lack of action. For those people with FASD the middle step, reflection, is faulty, works only sporadically, or is missing altogether. Reflection, something we do in a split second, is a very complicated function comprised of many inter-related thought processes, any one of which, if faulty, will radically alter the way one perceives relationships. Good cause and effect reasoning is also essential to motivation to do just about anything. This is particularly a problem in terms of motivating the individual to long-term changes, a primary reason why both rewards and sanctions, when used, must be immediate and why affected persons seem unable to delay gratification or work towards long-term goals. If you do not have good cause and effect reasoning, you “just don’t get it”.

Problems with the ability to generalize information

The ability to take information learned in one situation and use it to solve problems in another similar situation – the ability to generalize – is the essential thinking or problem solving process without which even marginal functions in an adult society is difficult to impossible to achieve. In FASD, this thinking process seems to lack movable parts; everything is seen as unprecedented, never having occurred before, and to which no previously acquired social and/or behavioral learning applies. People who are able to generalize see things as sets of shifting possibilities, depending on what has gone on before. People affected by FASD do not see those “possibilities”, only what is here and now. They are not flexible thinkers. Decision making is also governed by the ability to generalize. We use general rules of thumb – solution strategies – which we derive and remember from personal experience, and which worked before, to make decisions in new situations. These past experiences guide our thinking and provide a basis for making those choices.

For the person with FASD, choice making and problem solving are very difficult undertakings because they lack the ability to re-organize – in other words, generalize – this information and perceive new relationships among the pieces of a problem. In FASD, the first solution to a problem is usually seen as the only solution to a problem, even when it clearly does not work. People who cannot generalize then, are unable to develop an understanding about something new they come across based on similarities to, or differences from, something with which they are already familiar: i.e.: if a rifle is dangerous, then a handgun is too; if leaving your child unattended causes him to be apprehended, then arranging for his care will prevent that happening. It has been said that the Golden Rule of FASD is “Thou shall not transfer”.

Problems with understanding concepts and abstract thought

A concept, or idea is a mental {one that is held in the mind and not seen} category of things, events, occurrences, people, traditions, and society rules grouped together on the basis of commonalities. They are general ideas – the generalization dilemma again. They describe, in a nutshell, the sum total of society’s past knowledge, and experience in an area of learning and provide guidelines and parameters for acceptable function. Grasping concepts and how they relate to the individual, allows that individual to understand and deal effectively with the world {i.e.: time, money, numbers} and to predict how he needs to interact with future events {i.e.: honesty, integrity, responsibility, values}. If you cannot form ideas – concepts – and maintain and apply that learning, then you are forced to deal with every unfamiliar event or situation as entirely new – and again, previous learning does not apply.

Abstracts, very closely allied to concepts, can be defined as “a thought apart from any particular object or real thing not concrete, but somehow related to it”. In other words, a lump of sugar is concrete, the idea of sweetness is abstract; a moving car is concrete, the idea of danger associated with it is abstract; cash money is concrete, the idea of value related to it is abstract.

Abstracts and concepts work together to help us deal with life. For the person with FASD, who is unable – not unwilling – to conceptualize and abstract even the most basic human interactions with any success, life is spent walking on quicksand. Social rules are a quagmire and human language is full of words of great abstraction. Consider the words “if”, “when”, “maybe”, perhaps”, “then”, “soon”, “sometimes”, “later”, “either”, “or”, “should”, “could”, “would”, “but”, etc. What happens to the person who simply cannot process or make sense of what is meant by such abstractions?

To deal effectively with life and to function successfully, you must be able to conceptualize and abstract at a fairly sophisticated level of accomplishment. Persons with FASD are unable – not unwilling – to do this. They cannot begin to understand why they keep running afoul of our expectations for their performance, never mind predict how they should behave in the future or how we might react to that behavior.

Problems with perseverative behaviour

Perseveration is commonly described and thought of as some form of repetitive behavior – i.e. tapping toes, drumming fingers, knocking, pacing, etc. In persons with FASD , and particularly in adults, it manifests as a particularly rigid way of looking at things, a refusal to let go of an idea (rigid tenacity which can border on fanaticism); and/or a certain way of feeling or interpreting a feeling and refusal to consider any other explanation. It can also be seen as a narrow interest in something which excludes all others. Adults who perseverate “lock in” to their behaviour and are unable – not unwilling – to sort it out or make sense of it. Trying to “talk sense”, “rationalize” or otherwise intervene, especially using languages, makes the situation worse. They are unable to “let go” no matter what the negative consequence and are unable to see other possibilities. Adults who perseverate usually have great difficulty in seeing similarities and differences in behaviors and situations, along with problems in sorting and classifying sub-sets of those behaviors. Again, the first choice is seen as the only choice.

Problems with the ability to conceptualize, internalize and structure time

Time is an abstract concept; it is something which governs events, and the passage of which happens even in the absence of clocks and watches. People with FASD are largely unaware of time. It has little meaning for them and is not a valid method for negotiating a day, week, month, or year. Our culture works on time; it controls, to a very large extent, everything we do. The person with FASD who does not grasp the concepts involved, even if able to “tell time”, is still unable to internally structure “time” in a way which would allow for its use. The implications for independent function are not to be underestimated. Adults with FASD {not to mention children as well} do not keep appointments. They do not follow through on instructions. They do not remember when a meal time is; never mind when they – or the child – last ate. They do not show up for work on time, and do not come back from lunch on time. They seem oblivious to the days of the week and seasons of the year – all sequential cycles of time. They do not know whose birthday comes first, even when they know the actual dates for family members. They do not grasp that 7:55 and 8:00 are the same thing for all intents and purposes and are unable to organize their lives according to a time construct without years of specific teaching. They “tell time” using a digital watch (which has absolutely nothing to do with actual “telling time”) but are unable to generalize that skill (because it is not concept based) to an analog watch. If they finally master an analog watch with numbers, they will not be able to switch to an analog watch without numbers or only the 12, 3, 6 and 9 indicated. Again, generalization to a very slightly different situation.

Add to this the fact they have no “sense” of time passing, are often truly unable to differentiate between 15 minutes and two hours, perceive “early” and “late” very differently than we do and are unaware of how long it takes to accomplish a whole range of tasks and you begin to understand that the expectations for this group of people must be substantially altered. A major mistake made by all systems which deal with adults with FASD is to assume that because they can tell you the time using a digital watch {and since most of us use the same watches} they actually know what time is and how it works. Consider these: How can 60 minutes be one hour if 30 days is one month when 30 is a smaller number than 60, but a month is longer than a day? How can there be 24 hours in one day when there are seven days in one week? How about a.m. and p.m.? How can 7 o’clock occur twice in one day? How can the second 7 o’clock be at night when it is still light outside? How is the person with FASD supposed to hold all of this in his/her head, at the same time, all of the time?

Problems with short term memory

Memory is defined as the mental ability to store information for later use, and the capacity to retain and recall that past experience as required. A functional memory is essential for the use of critical thinking skills in all of the following areas relative to successful functioning, particularly as it applies to parenting: understanding truth, comparative judgments, making choices, following through motivation, responsibility, delaying gratification, and problem anticipation, recognition and solution. Problems with the correct storage, integration, or retrieval of information from memory will have a negative impact on one’s ability to adequately and accurately address a situation requiring a response from the individual. Adults with FASD (and children too) have what is known as “flow- through phenomena” – information may be learned, stored, and retained for a while, only to disappear without warning, and reappear just as suddenly, all with no predictable pattern – hours, days or weeks later. What can be said with certainty, is that this unpredictable pattern happens just often enough to convince those who do not understand, that this is deliberate “behavior”, under the control of the person with FAS/E. The reality is very different, and no one is ever more frustrated than the person with FAS/E, who must constantly deal with the reactions of others to this behavior.

Difficulties with sequencing – the ability to follow something in the order in which it is presented – also indicates a problem with short term memory, and means that information, when stored, is being done so in a random, haphazard fashion, in no predictable order. This has serious implications for being able to “tell the truth” and for being able to understand and make sense of something which has happened, information which one is given, or something one is asked or told to do. It does not mean the adult with FASD is a “liar” in the commonly accepted sense of the word. He/she is, however, unable to recall and/or make sense of past events in the logical, rational, sequential order we call “truth”. Confabulation occurs when interpretation of what has been incorrectly stored to begin with runs headlong into a distorted perception of the environment and one’s relationship to it. Even when information has been successfully stored and accessed, the individual with FASD must be able to interpret what he needs to do with that information, which, once again, requires the use of generalization skills linked to cause and effect reasoning, in addition to accessing a time construct, to make a logical, rational, and sensible inference about what should be done, and when it needs to be done.

Problems in all areas of processing information, particularly auditory

FASD is a serious information processing deficit which covers all four domains involved in processing information obtained from the senses, most particularly auditory information. Information is neurologically processed using input {recording information from the senses}, memory {storage for use}, integration {interpretation} and output {appropriate use of the first three}. While adults with FASD have significant processing deficits, they are nonetheless highly verbal, and often very articulate individuals, who give the appearance of being much more functional than they actually are, based on their use of spoken language. As a rule, we judge people on just exactly this – language use. With FASD, nothing could be more misleading or farther from the truth. Information processing deficits of the type universally found in FASD, mean that the individual does not – because he cannot – do well in any of the aforementioned areas of neurobehavioural function which are absolutely inseparable from acceptable social, emotional and behavioral functioning in adult society, no matter how verbal he/she is. The adult with FASD has the appearance of capability without actual, underlying ability.

Processing deficits with FASD mean that one cannot use language as a primary means of effective communication with the individual. Consequently, any language and cognition based treatment, intervention or parenting program will fail. Belief that the adult {or child, for that matter} with FASD – or one who remains undiagnosed and/or unsuspected – is cognitively aware and comprehending of conditions and circumstances and able to make changes based on his/her statements to that fact, will cause one to make critical errors in case planning, case management and case dispensation. This is equally true for social service delivery and the judicial system.

In FASD, the brain link between what is asked or required of an individual by a person, place, situation, etc. {information going in} and the action he/she needs to take {activitygoing out} is defective. Input and output do not equate. The behavior of persons with FASD is not non-compliant behaviour; it is non-competent behaviour.The behaviours and functions associated with FASD and pre-natal exposure to alcohol are not developmental delays. They do not go away over time, but merely change how they manifest themselves. In fact, these problems become more obvious with increasing age and our demands that all people become self-directed, self-motivated, self-controlled and self-“remembered”. Any attempt at treatment or intervention for child or adult is unlikely to succeed if we do not keep this information at the forefront of case management. Our lack of tolerance for behavior which falls outside the norm is understandable; our lack of knowledge, training and understanding of what causes this behavior and how one might more effectively and humanely deal with it, is not.

The problems as discussed above also impact significantly on children with FASD. The primary difference is that adults do not expect children to “think” on the same level as adults; they expect children to “grow out of” what they see as “stages” and believe that if given enough exposure to the “right” things – whatever they are – children will somehow, through osmosis, metamorphosis into functioning people. When that does not happen, however, they typically impose more and more stringent sanction for behavior which is no longer developmentally acceptable.

Children with FASD are very difficult to parent under the best of circumstances. They do not process or make sense of their environments any more than adults do. They may also be very hyperactive and have problems paying attention to just about anything. They are highly suggestible, impulse drive, and repeat behaviors which have had negative outcomes over and over. Many are, or quickly become, oppositional and defiant and are highly intolerant of any kind of verbal restriction. Problems with eating and sleeping are common, and many have other significant medical problems as well. Children with FASD have trouble with attachment and bonding – even in the absence of abuse, neglect and multiple careviging – due to their problems with cause and effect. Attachment is a primary cause and effect relationship and this may be the first place this problem shows up. Multiple care giving can be disastrous for these children.

Their problems with social, behavioral and academic school learning are usually significant, even in the absence of mental handicap. Most of them function, by IQ measurement, too high to qualify for more than minimal service in school. Their problems in the school can be overwhelming and frequently blow back on the parent or caregiver. The average child or teen with FASD is very verbal and talks a lot, and is subsequently thought to be brighter and more functional than he/she actually is, leading to the belief that what one sees is “behaviour” and not organicity. They appear to be the product of “poor parenting”. It is very easy for systems to fall into the trap of blaming the parent, and while poor parenting and unhealthy environments definitely make things worse, they do not cause the problems to start with.

Children and teens with FASD are very tactile and have many problems with inappropriate touching, even in the absence of abuse. They are ready targets for those who would take advantage of them, and frequently the subjects of sexual abuse themselves. A significant proportion of these children will go on to become abusers of other children. Treatment for this group of individuals has not been effective and this lack is cause for very serious concern for their futures.

They are very much at risk for physical abuse in the community at large and in dysfunctional homes due to the chronicity of their various behaviors. They frequently have a very high pain tolerance, and would not necessarily respond to physical abuse as would another child. Injuries and illness which go untreated for longer than would be expected are common in this group of children, even in stable homes, due to this tolerance for discomfort and pain.

Children with FASD require early resolution of placement issues, and good, skilled case planning to meet their long term needs. Multiple placements must be avoided. They must have, as an absolute minimum, stable, consistent, caregiving, with a caregiver able to learn the specific skills which are required to maximize functional potential in this group of children. To reach any kind of sustained function within individual parameters of ability, they must have:

- Constant, total supervision

- Highly structured, significantly altered physical environments

- Different communications techniques

- Mediated learning

- Labour intensive, time consuming interventions

Regardless of age or IQ. Individuals with FASD are not candidates for independent living as adults without extensive, intensive, comprehensive, and continuing supports in place. This is as true for the affected individual with the IQ of 90 as for the individual with an IQ of 68.

More Information and Resources:

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

NIAAA supports and conducts research on the impact of alcohol use on human health and well-being. It is the largest funder of alcohol research in the world. NIAAA-funded discoveries have important implications for improving the health and well-being of all people.

Making a Difference Working with students with FASD

In some classrooms, FASD is such a large and intractable problem that we may not even be able to acknowledge it. Knowledge and understanding of FASD helps make sense of the challenges facing students with the disability.

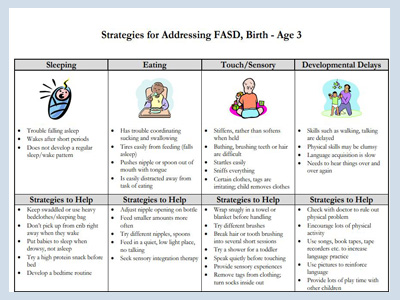

Strategies for Addressing FASD

A simple yet handy chart for Strategies to Address FASD form and then onto adulthood.

JUVENILE COURTS: What Works With Kids With FASD?

A presentation by William J. Edwards, Deputy Public Defender Office Of The Public Defender Los Angeles County, California on the Relationship Between Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Child Maltreatment

Legal Advocacy in New York –Accessing Services and Supports for Children and Adults with FASD

Disability Rights New York is the statewide Protection and Advocacy System and Client Assistance Program DRNY advocates for New Yorkers with disabilities to enable them to Exercise their own life choices, Fully participate in their communities, Enforce their civil and legal rights.

FASD: Why Can't We See it?

A presentation by Larry Burd, PhD Director, North Dakota Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Center

Reach to Teach Children FASD

Reach to Teach is a valuable resource for parents and teachers to use in educating elementary and middle school children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). It provides a basic introduction to FASD, which results from prenatal alcohol exposure and can cause physical, mental, behavioral, and/or learning disabilities, and provides tools to enhance communication between parents and teachers.

Parenting Tips: Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

A child who has FAS is very likely to steal from the parents, lie to them, and sneak around. The parents have to understand that the child is not doing these things to them. He is simply getting through his day in the way in which his mind allows him to. He is not actively trying to harm the parents or destroy his relationship with them.

Child Welfare Services for Addressing the Needs of Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

Of all the substances of abuse, including heroin, cocaine, and marijuana, alcohol produces by far the most serious neurobehavioral effects in the fetus.”

Let’s Talk FASD: Parenting Guidelines for Families

LETS TALK FASD presents parent-driven guidelines evolved from the first hand experience of those living with FASD and those that care for them and respond to a community need for tips, techniques and strategies that are empirically proven by parents themselves.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FASD

CDC is working to make alcohol screening and brief intervention a routine element of health care in all primary care settings. Find FASD online training and resources for healthcare professionals.

Women & Children’s Hospital of Buffalo: Special Diagnostic Program

The Special Diagnositc Program seeks to meet the diagnostic and treatment needs of patients with known or suspected prenatal exposures to neurotoxic substances, such as alcohol. The program works with families to help them to better understand their child’s diagnosis, and help them obtain needed community and/or school services for their child