“There are only two lasting gifts we can give our children: One is roots – The other is wings”

Hodding Carter, Sr.

Leaving home is a challenging period in nearly everyone’s life, fraught with conflicting feelings and needs: the earnest desire for independence and autonomy, alongside the fear of failure, and continuing sense of dependence on parents and others in authority over one’s life.

In a sense it is an assertion of selfhood and a separation from others, particularly parents, that begins in the two-year old state, has its stronger and weaker moments over the childhood years, comes on strong in early adolescence and reappears full force in late adolescence. The acknowledged goal in this society, at this time, is to leave home “successfully” – that is capable of independently supporting oneself financially, physically, and even emotionally.

The interim step is a sort of semi-independent state offered by college dormitory living, military housing, or the first apartment shared with others – with a strong cord still tying the young person to the parent’s home: many meals, laundry and some of the financial support often still coming from the parents. Ultimately this is to lead to a “home of one’s own,” often with a partner (through marriage or other long-term commitment) and possibly children.

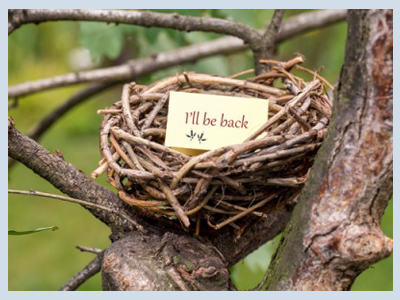

Much has been written in the past few years in sources as varied as scholarly journals and women’s magazines about the difficulty many young adults are experiencing today as they attempt to leave home and the “new” phenomena of adults in their late twenties and even thirties who have either never lest the nest, or who have ventured out only to return to the nest. If this leave-taking is difficult, complex and conflict-filled for most young adults, it is doubly so for adoptees.

One of the chief emotional issues adoptees face throughout their lives is learning how to cope effectively with the feelings that are associated with separation and loss. Leaving home is the ultimate separation, and not only has its own complicated challenges, but can trigger all of the feelings the adoptee may have about their own separation from the birth family and subsequent separations from foster families.

In this context any attempts by the adoptive parents or others to assist the young person in gaining the skills and confidence to become successfully independent can be seen as one more rejection in the adoptee’s life. Encouragement to seek one’s own way can trigger deep-seated fears of abandonment. On the other hand, most adoptees are going through dealing with these issues around separation, loss, rejection, abandonment, and grief are also likely to be experiencing the normal developmental stage of late adolescence: the desire and need to pull away from the parents to establish one’s own identity and assert one’s status in life.

The multitude of conflicts generated by these feelings can then expand to encompass fear of failure, anger, guilt, self-doubt, and greater feelings of helplessness and dependence. Some adoptees are able to work through these complex feelings quite successfully and emerge unscathed and stronger with a clearer sense of self.

Others can feel defeated by these waves of conflicting needs and emotions and can manifest this in several ways. Three of the most common such manifestations include:

- Denial of Conflict: Any feelings of fear, anger, failure, etc. are overridden by a furious need to stand alone, to “prove” oneself capable, to not need anyone for anything. A young person denying any of the conflicting feelings often pushes for independence sooner than non-adopted peers and pushes away from the family forcefully. This can leave parents feeling rejected and bewildered and can set up a break down in the parent child relationship that can be difficult to mend.

- Paralyzing fear of leaving home that results in a “self fulfilling prophecy” of failure and refusal to leave and/or frequent return trips to the parent’s home. Adolescents who become paralyzed by their fears of leaving home can regress in their behaviors, fail in school, and become incapable of sustaining themselves outside of the parents home.

- Inability to plan for or think about leaving resulting in self-sabotage of positive steps towards independence and replaced by a set of circumstances that force the leaving to occur in an unplanned crisis. The crisis can be unplanned pregnancy, delinquent or criminal behavior, substance abuse or other behaviors that set up the youth being “thrown out” by the parents.

In working with teens as they go through these challenges, it is important to remember that the word “independence” is truly misleading. None of us is truly independent. We always need and rely on others in order to have a successful and satisfying life. sometimes we rely on others for physical needs (i.e. medical care), sometimes for emotional needs (sharing holidays with extended family, mourning a death, etc.), or sometimes just for recreational needs.

A better work is “interdependence” as we become less dependent on parents and move into the adult world – we still need to recognize our interdependence with other people. Helping young people accept this concept helps them make the transition from home to adult living more successful and less stressful.

Remember – the goal is giving wings to our young people is to help them develop wings that are strong enough to really fly!

Tips for Adoptive Families

There is no surefire way to ensure that an impending move toward greater independence; high school graduation, etc. will proceed smoothly for any particular young person. However, there are steps parents can take (and advocates can assist parents to take) to help ease the conflicts associated with this transitional stage. These include:

- Clarify values: Whose value is it that your son or daughter must graduate from high school? Or go to college? Or set goals for a professional career? Whose values – (yours or your child’s) will set the pace for the transition from adolescence into young adulthood? What will the impact be on you and your child if your values clash at this time? Can you convey your continuing love for and commitment to your child even if she chooses a path other than the one you had hoped for?

- Be a role model: Adolescents need role models of how parent-child relationships can, and do, continue even when the child becomes an adult. Show by example, how adult family members still care for one another, communicate, stay in touch, remain involved in each other’s lives. Show that physical separation (i.e. no longer living under the same roof) does not mean relational or emotional separation. Talk about these relationships, perhaps watch a video or read a book together that shows examples of adult/adult parent child relationships. Talk about how your relationship will change and in what ways it will not change as you move on into this next phase of life.

- Keep a room open: If at all possible, keep your child’s room open for them as a place to stay when they come home to visit. This concrete reminder that they still have a place in your home and thus in your life, and in your family, can be crucial at this time.

- Make future plans together: A fishing trip, a shopping trip, going out for a future birthday – plans to be together in the future serve as a reminder that you are still involved in each other’s lives.

- Develop concrete skills: Often children who are in special education or vocational rehabilitation services receive “Life Skills” classes, which include checkbook management, grocery shopping, me

nu planning, and other basic skills. However many average and college prep students do not get these classes. The very thought of paying their own bills or balancing a checkbook can be overwhelming. Be sure your teen has the important life skills he or she will need. These can include:- Financial record keeping and budgeting

- How to use phone book and public transportation

- Basic knowledge about sexuality and birth control

- Household management skills especially in reporting problems (i.e. to a landlord)

- Nutrition information, menu planning, grocery shopping

- Personal hygiene and health care

- How to not only obtain, but how to maintain, a job

- Re-visit the life book: Try to help your son or daughter find ways to develop a sense of wholeness in her life, to allow the past and the present and the hopes for the future to comfortably co-exist.

- Be open to utilizing professional resources such as:

- Mental health services

- Health care Providers

- Adult/continuing education

- Vocational rehabilitation services

- Career counselors

- SSI, other public benefit

- Learn to recognize, appreciate and celebrate success!

Source: Coalition 2006 Workshop Presentation by Sue Badeau, Badeau Consulting.