|

In general, the fight for Adoptee Rights in New York, and in many states around the country, centers on legislation to restore adult access to their original birth certificate (OBC). From 1873 to 1924, adoption records in New York were public record [1]. Since 1938, New York law calls for the OBC to be sealed upon the finalization of an adoption and a new amended birth certificate (ABC) to be issued to the adoptive parents stating their names and the new, legal name of their child. The ABC is used for legal purposes that require a birth certificate. The OBC is locked away forever. Under the current law, no one can access the OBC; not the adopted person, not the adoptive parents, nor the birth parents, though there was always a provision that the court could open the records “for good cause[2]”.

Since the late 1970’s, several pieces of legislation to change access laws in New York have been proposed. The opposition comes from the State Bar Association, Surrogates Court judges and some members of the legislature who purport the myth that a birth mother being contacted by her now adult child could have catastrophic results. This last legislative session in New York, there were two pieces of proposed legislation that both claimed to be “Adoptee Rights” bills.

One of the proposed pieces of legislation, S5169A/A6821A, would allow an adoptee, upon reaching the age of eighteen, to request their previously sealed, original birth certificate to be released from vital records just like any non-adopted citizen. This bill continues to sit in committee.

The other, A5036B, was passed in the Assembly in June and, in what was virtually the final minutes of the 2017 session, was pushed through the Senate and passed. Currently, it waits to be transmitted to Governor Cuomo for his consideration.

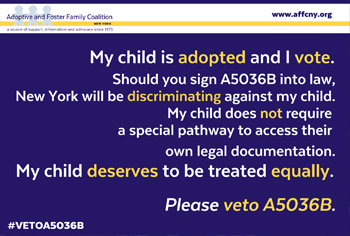

It is noteworthy that the very community this bill purports to serve have largely come together in resounding opposition to A5036B. Individuals, groups and organizations from across the country have urged Governor Cuomo to veto A5036B for a variety of critical reasons. Here, we call attention to some of the more egregious provisions of A5036B that does not show New York as a leader in adoptee rights but rather as a state willfully ignorant to the realities of adoption today.

- A5036B fails to achieve its purpose. Restoring the rights of adoptees to be treated equally as those non-adopted is a civil rights issue. Treating one class of person differently than another based on the circumstances of their birth is discrimination. A5036B creates a new judicial path that ONLY adopted people must take to regain access to their own legal documents. No other party, group, or individual is forced to go through such lengths to access their vital record. A5036B does not end adoptee discrimination in New York, it only changes the mechanism of that discrimination.

- A5036B permanently and legally infantilizes adults. The legislation requires adult adoptees to have parental permission to access their documentation. Any other person in the state can access their birth certificate without having to notify their parents, but the language of A5036B states that adoptive parents are given “due notice” and birth parents are to be asked for their “consent” to be given before the adopted person would gain access to an unaltered original birth certificate. No other group of adult people need parental permission for such documents, nor is there precedent, aside of individuals with significant cognitive or mental issues, of treating adults as minors.

- A5036B codifies unprecedented and unrealistic rights of lifelong confidentiality to birth parents. While there are many individuals, including leaders in Albany, who believe that birth mothers who relinquish a child to adoption were “promised” lifelong confidentiality, the facts say otherwise. According to research, “courts have found neither statutory guarantees of, nor constitutional rights to, anonymity for birth mothers, and that the documents birth mothers signed surrendering parental rights did not promise anonymity.[3]” What A5036B will establish and codify into New York law for the first time is the legal anonymity of birth parents and essentially make them a special class with no legal justification except their personal preference. There is no other group of individuals who have the ability to have confidentiality guaranteed by the state, nor are there any other circumstances where biological parents are given the right to have their name removed from birth records.

- A5036B claims to do the impossible. The core issue of OBC access is not about search and reunion, but removing discrimination and restoring equality. Adoptees and birth parents have searched and found each other for decades without access to the OBC. The state has never been able to promise confidentiality. Social media, scientific advances in DNA testing, and genealogy search techniques have removed anonymity from the picture for society altogether. Still, A5036B ignores this reality. By codifying erroneous mythology, New York would make promises that cannot be kept. A5036B would open the state to liability should the very real eventuality that a birth parent is given a redaction and is later found through other methods.

- A5036B creates an unneeded responsibility for the state. A5036B calls for the Department of Health to become a state-appointed confidential intermediary and “search” for birth parents in order to gain permission to release the OBC in full. There is already a six to eight month wait for registration and information based on the state’s Adoption Registry, yet now the same department is expected to “find” people based on records that are decades old within 120 days. There is no mention of how staffing, training, or education will be ensured for this responsibility. There is an added concern regarding the state’s liability should that initial state contact be seen as problematic to the outcome of a successful relationship. A5036B assumes, contrary to research-based facts, that a woman who relinquished her child to adoption would prefer having notice given by an unknown government worker rather than be privately contacted by that actual child.

- A5036B will have negative fiscal impact. A5036B is an unfunded mandate documented as having no fiscal implications for state or local governments attached.[4] Under the bill, the Department of Health is required to search for and notify all listed birth parents in order to inform the court. Advocates have conservatively estimated that as many as eight thousand adoptees could be expected to request their OBC within the first year. The costs associated for “searching” for the birth parents for their permission have been projected to be upwards of three to six million dollars[5]. Nothing in the bill language accounts for this required expenditure. Meanwhile, under the “other” version of the bill, adoptees could apply for their birth certificates through the preexisting system and would pay the standard fee, creating a positive fiscal impact.

- A5036B will overburden the court system. Procedures such as attorney representation, the barrier fees may create or even who could rule and approve access are not clearly defined in this legislation. A5036B calls for a “written order” issued by the court which strongly alludes to a judge’s direct involvement. Despite this, the bill’s sponsor recently stated that a court clerk could approve requests. This contradiction speaks to just how ill-defined procedures are in this bill. The courts already exceed the targeted timeframes for permanency hearings and other processes[6] relating to the direct care of minors in foster care and waiting for adoption. How can our state’s already overburdened court system accept the possibility of an influx of another eight thousand adults when we already know the system is backlogged?

- A5036B would release a certified copy of the birth certificate which technically allows for the possibility of a person having two separate legal identities. A birth certificate is supposed to be the legal record of a birth and is used to both prove citizenship and identity. For this reason, most adoptee rights legislation calls for the release of an uncertified OBC so it cannot be used for legal purposes. A5036B would release the foundation of duplicate identities. The redaction of a birth parent’s name would also permanently alter legal documents and create far reaching implications for geological research. A5036B also has no provision for the descendants of the adoptee, leaving future generations no recourse.

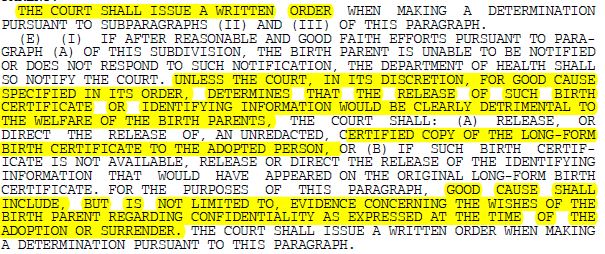

- A5036B leaves too much open to interpretation and the discretion of the courts. There was always a line in adoption law that stated the records could be opened by the court for good cause, such as a medical necessity[7]. Yet, we know through practice that even when an adoptee or birth parent has vital medical needs, the judges almost never grant access to the records. Somehow we are to believe the same courts and judges that have routinely denied access, now will be somehow compelled to change their preferences. A5036B states that if the state fails to contact the listed birth parents then, “unless the court, in its discretion, for good cause specified in its order, determines that the release of such birth certificates or identifying information would clearly be detrimental to the welfare of the birth parents… good cause shall include, but is not limited to, evidence concerning the wishes of the birth parents regarding confidentiality at the time of the adoption or surrender.” There is not a provision in A5036B that truly compels the court to err on the side of the adoptee; rather, language would allow a judge to use any possible reasoning to deny the release. If a birth parent has not been successfully contacted by the state or is deceased, the presumption is that their intellectual and emotional perspective has remained the same for decades. There is nothing in the language to prevent a judge who may have formerly served as an adoption attorney, to cite his memory of a birth mother’s concerns about rumors and therefore deny the now adult adoptee. The ambiguity of this provision could burden adopted people and lead to arbitrary and capricious court decisions.

- A5036B further victimizes and outright fails persons adopted from foster care. There is already no recourse for adoptees whose birth parents rights are terminated in court as the New York Adoption Information Registry does not allow those birth parents to register: “A birth parent may not register unless the adoptee is eligible to register and the birth parent’s consent to the adoption or signature on an instrument of surrender was required at the time of the adoption.[8]” With no notice that those adopted from foster care would be barred from petitioning the court, the language of A5036B would suggest that the Department of Health would have to conduct a “search” and request the consent of birth parents as well. An adopted citizen, whether adopted though foster care or as an infant should hold the same human right to access their documentation, yet it is concerning to think that a parent, who is often found to have harmed a child (hence the removal of the child through the courts) would be later be provide the power to consent or not.

- A5036B also fails to address situation of step parent adoptions. Unlike tradition adoptions, the majority of those adopted by a step parent are aware of their true parentage. In the case of a step parent adoption, there is no need to waste the courts time or “searching” for a known birth father who is deceased or has voluntarily relinquished rights to a child in order to gain their permission. With an national average of 37% of adoptions estimated to be step parent or relative adoptions and 42% of adoptions coming through public foster care[9], A5036B only addresses the less than 15% of adoptees adopted to non-relatives privately.

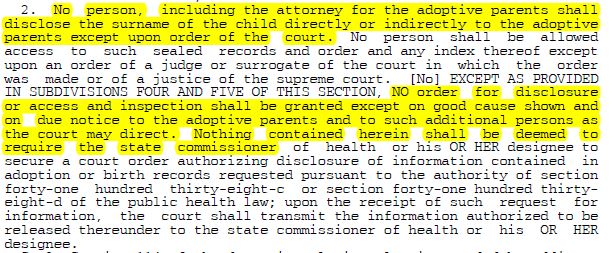

- A5036B would criminalize the preferred practice of open adoption. If signed, the law would be that “no person, including the attorney for the adoptive parents shall disclose the surname of the child directly or indirectly to the adoptive parents except upon order of the court”. With 95% of current adoptions having a degree of openness, including the exchange of identifying information between parties (often long before the actual birth of the future adoptee and involvement of the courts), this language criminalizes adoption professionals, birth parents, adoptive families, and adoption attorneys. At best, the unforeseen consequences of this passage would create a situation where the already overburdened court system would have to approve of open adoption contact, creating yet another barrier to adoption.

- A5036B sets a negative precedent for other states looking at this issue. New York is not the first state to revisit an adoptee’s right to access their OBC. Likely it will it not be the last. While other states have successfully implemented changes in law (OR, RI, NH, I, AL, ME, CO, and HI), there are many others who will look to New York for their leadership. A5036B is opposed by almost every international, national, and state-based adoptee rights organization as it would enact model legislation that would allow this legal discrimination to be replicated.

- A5036B is not a “good first step”. Proponents of A5036B claim that a simple solution such as S5169A/A6821A “will never pass” due to the legislative process in Albany. The current environment around this legislation seems to be the belief that once this first backwards step is taken, that the issue could be revisited and “corrected” in the next year when the opposition in Albany sees that nothing horrible has happened by allowing adult adoptees access to their original birth certificates. This is disingenuous. It is hard to imagine that one year of statistics will be enough to alter the mindset of those hardwired to believe such mythology when the reports of other successful states, research, facts and countless anecdotal evidence and testimony has done nothing to change their viewpoints.

- New York will be saddled with A5036B for another generation if not more. Not only is A5036B problematic due to all the reasons above, historically states have been reluctant to revisit a legislative issue after changes of this scope. In Ohio, it took advocates over 24 years to correct earlier legislation. Montana is still facing problems due to “reform” made in 1997. A decade after Massachusetts changed their access legislation in 2007, they are finally primed to make the necessary changes. It is worth noting that Massachusetts only has to remove nineteen words from the current law to achieve true adoptee equality, where A5036B’s objectionable word count is much greater than nineteen. If we don’t force New York to get Adoptee Rights correct the first time, the reality will be that our children will be the one’s fighting to clean up this mess.

While it is true that if passed A5036B could allow some adult adoptees access to their original birth certificates if the state finds their birth parents and those parents give consent, it is also conceded that other adoptees might get access to a doctored OBC if the court deems it so; however, this is not a case where something is “better than nothing”. The long term implications, negative reach, unforeseen consequences, and possible liabilities turn A5036B into a very dangerous proposal. Adoptees deserve the right to equal treatment under law. Instead of shining a light of leadership on New York State, A5036B is mortally flawed. A5036B is not about equality and must not become law.

For all these reasons, we continue to strongly oppose the passage of A5036B into law.

Please join us in asking Governor Cuomo to veto A5036B.

Order #VetoA5036B postcards today! Fifteen Reasons Why A5036B Must Not Become Law in New York

DOWNLOAD and print: Fifteen Reasons Why A5036B Must Not Become Law in New York