Health, Disabilities and Special Needs

Deciding to adopt a child with additional challenges can be scary. Yet, if you conduct your own honest self-assessment and discover that you are among those who are able and willing to proceed with this type of adoption, it can be an extremely rewarding experience.

Health Care Advocacy

Foster, kinship and adoptive parents can be a critical advocacy force to ensure that children services to enhance their healthy development and prospects for permanency. Health Services Advocacy is a must learn skill for foster and adoptive parents caring for children frequently enmeshed in multiple systems of care.

Special Needs

The term special needs is a catch-all phrase which can refer to a vast array of diagnoses and/or disabilities. Children with special needs may have been born with a syndrome, terminal illness, profound cognitive impairment, or serious psychiatric problems. Other children may have special needs that involve struggling with learning disabilities, food allergies, developmental delays, or panic attacks. The designation “children with special needs” is for children who may have challenges which are more severe than the typical child, and could possibly last a lifetime.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) is an umbrella term describing the range of effects that can occur in an individual whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy. These effects may include physical, mental, behavioral, and/or learning disabilities with possible lifelong implications. Its impact on the ability to parent cannot be overstated.

Parenting a Child with Special Needs

As prospective parents, begin with a self-assessment: consider your motivations for adopting. Then ask yourself if you have the coping skills, personality, attitude and lifestyle to move forward and take in a child. “Those considering adoption have to think about the numerous loss, grief and attachment issues that can impinge on the cognitive development, motor and self help skills of a special child,” said Vali Ebert, Executive Director of Adopt a Special Kid (AASK) in Oakland, CA. Some kids are under-socialized and need help with all sorts of routine tasks, including proper hygiene or eating skills, she adds. “In addition, parents must become instant advocates with educators, counselors and others who interact with their child. Children with extra challenges often also need access to occupational and physical therapies and equipment.”

Crucial Points to Consider:

- Make sure you and your spouse wholeheartedly want to adopt. Sometimes, Mom wants to adopt, but Dad doesn’t. “That’s not a good idea,” said Ebert. Don’t adopt thinking that the child with special needs will help cement a family or save a relationship.

- Nothing could be further from the truth. Special needs can be extremely demanding and can threaten a relationship. Like it or not, children with extra medical, emotional and behavioral problems can subconsciously work to divide a family.

- Don’t adopt just because you want one of your children to have a sibling. Adoption is not about a sibling’s issues, it’s about meeting the needs of the child to be adopted. Be aware that adjustment periods can and often do last a longer period of time when a child has special circumstances. Realize that you will need patience, ingenuity and strength to take on the additional challenges. Make sure you have or will have a flexible schedule to accommodate the child’s medical needs. Understand that these kids need an extraordinary amount of love and attention, even when they may not be able to show love to their new parents.

- Don’t transfer your expectations, sadness or anger onto your adoptive child. “One must be satisfied with where their child is and his potential,” said Ebert. “They cannot have fantasies about a child or his abilities because this places an enormous burden on the child — it sets him up for failure.”

- There are more than a handful of people who have examined all of the issues of taking in child with special needs and have decided to adopt. “Some people view adoption of a child with special needs as a public service — that they are helping the community at large — beyond just helping a particular child,” said Dr. Paul Denhalter, former Executive Vice President of the National Council for Adoption in Alexandria, VA.

- There are people, too, who gain great satisfaction from adopting a child who needs total care and seemingly will not progress compared to a child who will be able to partake in “normal” family activities. According to the experts, what seems to appeal to those who take in a “total care” child is their ability to improve the quality of the child’s life.

- “What they find rewarding and joyful is their ability to encourage the child to make small verbalizations or to respond to their presence with laughter or some other behavior,” said Denhalter. “Once we placed a total care child in a facility and she was frowning and scowling when I initially saw her,” he said. “Then, every month that I saw her after that, her face gradually softened and soon she was smiling. Little things like that unfold. It’s wonderful.”

Additional tips for adopting a child with extra challenges:

- Get training on being an adoptive parent before you bring a child into your home. Look for information on the Internet on adopting and raising a child. Use your adoption agency as a resource to identify therapists, places for financial support or organizations for respite care. Locating help early on can prevent serious problems from arising later.

- Get a specific background and profile on the child, including, if possible, a clear, medical profile. “If you don’t have sufficient background information on the child, take the child for a psychological and physical exam before agreeing to take him in,” said Denhalter. “It’s different, however, with babies because they lack a psychological background.”

- Understand the subsidies available for children with special needs. Get information through your agency and follow up with state or federal agencies that provide funding. “Never waive any subsidies because they might be necessary later and you’ll be unable to get them back,” said Denhalter. “It’s imperative to keep open connections that have been established.”

The first few months when the child moves into the family is going to be the roughest. “During this period, adoptive parents can get referrals through their adoption agency to hook up with a support group,” Denhalter said. Parents cannot immediately expect their child to be “grateful” for rescuing him and then to instantaneously love and adore them. Children, like most of us, cannot turn their feelings on and off. Coming to grips with strong emotions is a process that takes time. “These kids have suffered tremendous grief and loss — they may not be capable of showing a lot of love even though they need large doses of love from you,” Ebert said.

Parents must be able to accept this. It’s not uncommon for adoptive kids to not even feel grateful for being put in a new home. Even if they have been abused in the past, their biological parents are the people they know, regardless of their actions. In their minds, the adoptive parents have uprooted them — not rescued them. “In most cases, kids forever yearn for their birth family,” said Ebert.

The Five stages of placement when adopting a child:

- First, is the honeymoon period in which the child acts like a guest, does no wrong and the parents think they’ve found the ideal child.

- Then, the youngster reverses his behavior and pushes all limits to see what it takes to be rejected again. At this point, parents may question why they took in this child.

- Stage three is disillusionment. Parents begin to question what they did to themselves by adopting the child.

- If they can survive stage three, they can reach stage four — the coping level. The child is still testing his parents, but now they have learned how to control things better.

- Ultimately, parents reach the fifth level — the interaction stage. This is when a good working unit is established and a real feeling of family develops. During this fifth stage, parents think, “l can’t imagine what life would be like without this child.”

A healthy adoptive family doesn’t require a child to give up his loyalties or ties to his birth family. Some kids even stay in contact with their relatives. Adoptive parents will allow their children to talk about their birth family members, keep their memorabilia or presents from them and in general, share their feelings about them.

“Staying in touch doesn’t always mean physical contact,” said Ebert. “It means that parents cannot set up a loyalty conflict with their children because it’s a no-win situation.” Often, a couple or family who adopt a child with special circumstances experience tremendous fulfillment, said Denhalter. “They are providing emotional and financial support for a child who might otherwise live his or her childhood in extended foster care or an institution. It can be a truly enriching experience.”

Source: Judith Loseff Lavin, Reprinted with permission from the Fall 2002 Newsletter of Jewish Children’s Adoption Network. Judith Lavin and her family spent nearly 16 years struggling with and triumphing over the complex medical challenges faced by her two daughters. Lavin, the author of Special Kids Need Special Parents (Berkley Books, @2001), and a former journalist with the Chicago Sun-Times lives in Chicago. For more information see www.parentingchallenges.com

More Information and Resources:

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

NIAAA supports and conducts research on the impact of alcohol use on human health and well-being. It is the largest funder of alcohol research in the world. NIAAA-funded discoveries have important implications for improving the health and well-being of all people.

Making a Difference Working with students with FASD

In some classrooms, FASD is such a large and intractable problem that we may not even be able to acknowledge it. Knowledge and understanding of FASD helps make sense of the challenges facing students with the disability.

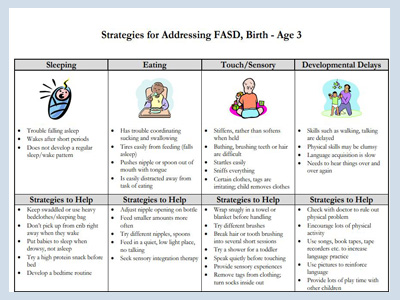

Strategies for Addressing FASD

A simple yet handy chart for Strategies to Address FASD form and then onto adulthood.

JUVENILE COURTS: What Works With Kids With FASD?

A presentation by William J. Edwards, Deputy Public Defender Office Of The Public Defender Los Angeles County, California on the Relationship Between Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Child Maltreatment

Legal Advocacy in New York –Accessing Services and Supports for Children and Adults with FASD

Disability Rights New York is the statewide Protection and Advocacy System and Client Assistance Program DRNY advocates for New Yorkers with disabilities to enable them to Exercise their own life choices, Fully participate in their communities, Enforce their civil and legal rights.

FASD: Why Can't We See it?

A presentation by Larry Burd, PhD Director, North Dakota Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Center

Reach to Teach Children FASD

Reach to Teach is a valuable resource for parents and teachers to use in educating elementary and middle school children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). It provides a basic introduction to FASD, which results from prenatal alcohol exposure and can cause physical, mental, behavioral, and/or learning disabilities, and provides tools to enhance communication between parents and teachers.

Parenting Tips: Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

A child who has FAS is very likely to steal from the parents, lie to them, and sneak around. The parents have to understand that the child is not doing these things to them. He is simply getting through his day in the way in which his mind allows him to. He is not actively trying to harm the parents or destroy his relationship with them.

Child Welfare Services for Addressing the Needs of Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

Of all the substances of abuse, including heroin, cocaine, and marijuana, alcohol produces by far the most serious neurobehavioral effects in the fetus.”

Let’s Talk FASD: Parenting Guidelines for Families

LETS TALK FASD presents parent-driven guidelines evolved from the first hand experience of those living with FASD and those that care for them and respond to a community need for tips, techniques and strategies that are empirically proven by parents themselves.

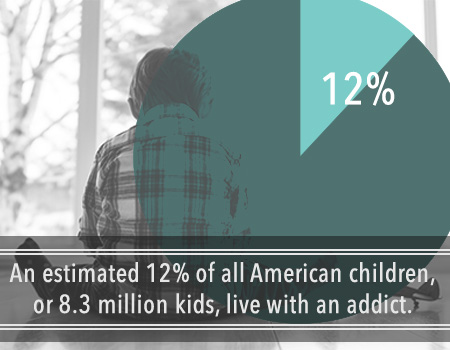

Addiction and Parents: Reaching Out

What can we, as foster parents, relatives, adoptive parents and professionals do?

Planning for the Future: a Guide for Families and Friends of People with Developmental Disabilities

This guide is intended to help you plan for the personal and financial future of your family member with a physical, mental or developmental disability. It will cover trusts and estates, wills, government benefits and services.

Psychotropic Medication and Children in Foster Care

Medications can help children and teens in foster care, but they can also further impair them, derail them, and sabotage them. Without a clear understanding of their mental health issues, misdiagnoses can be made and incorrect medications can be prescribed.

A Medical Guide for Youth in Foster Care

It can be really challenging when you’re in foster care, because there are laws and regulations that apply specifically to you. They affect who can give permission for your health care, the services and treatments you receive, and who pays for them.

Caring for Children with HIV and Special Needs

Caring for Children with Special Needs is written for parents, foster parents and other caregivers raising infants, children and adolescents with HIV. This 293-page notebook is a resource manual that provides information and support for some of the day-to-day issues caregivers face.

Dual Diagnosis: A Guidebook for Caregivers

This guidebook gives caregivers the tools they need to understand how mental illness might look in a person with a developmental disability, and information on what to do and where to go for help. It was written in order to help caregivers to partner with health care providers.

OPWDD’s Guide to Understanding Supports and Services

OPWDD's Guide to Understanding Supports and Services. The Guide was developed to inform families about the wide range of supports and services available to qualified individuals and to assist them in accessing those services for their loved one with a developmental disability.

Parent to Parent New York Health Care Information and Education Center

Parent to Parent of New York State builds a supportive network of families to reduce isolation and empower those who care for people with developmental disabilities or special healthcare needs to navigate and influence service systems and make informed decisions.

Working Together: Health Services for Children In Foster Care

This manual is designed to support foster care and health services staff in focusing attention on the critical issue of adequate, timely health services for children in foster care.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FASD

CDC is working to make alcohol screening and brief intervention a routine element of health care in all primary care settings. Find FASD online training and resources for healthcare professionals.

Women & Children’s Hospital of Buffalo: Special Diagnostic Program

The Special Diagnositc Program seeks to meet the diagnostic and treatment needs of patients with known or suspected prenatal exposures to neurotoxic substances, such as alcohol. The program works with families to help them to better understand their child’s diagnosis, and help them obtain needed community and/or school services for their child